The benefits of gesture in CLIL classes

Example in a natural science class

(Before reading this article, you may be interested to read a little on some background research regarding CLIL in Spain...)

If you are a natural science teacher giving a talk on the parts of the tree, you will undoubtedly use a slide projected on the screen showing the various parts of a tree in English or possibly students may have a textbook with a similar diagram they can refer to. Research has shown that if we can get our students to enact that vocabulary in some way, retention of those words will be more efficient (Kelly et al. 2009, Macedonia and Knösch 2011, Tellier 2008). With the diagram on the screen as a reference, transfer those words to gestures and ask all students to gesture likewise. Spend a little time on this and ask students to say the word while gesturing and correct pronunciation where necessary. Students will probably also need to write these words in a notebook. A sketched picture would be preferable to a translation only (or perhaps both) or even a copy of the diagram for them to add the written words. How the students annotate depends on the teacher's preferences although, according to a recent lecture I heard by Pavón (2018), the annotation system and the inclusion of translation should be systemized and consistent throughout the course.

The rationale is that you will now have a visual reference for your technical words, which you can refer to at any time. Remember that it is important to be consistent and always use the same gestures. You will not always have the diagram on the screen but you can perform the corresponding gestures whenever you need to. Your students may not initially remember the spoken English words on re-gesturing the technical language but they will invariably understand the word your gesture refers to so that you do not need to resort to using the mother tongue. With some recycling of these gestures and their spoken equivalents, students will soon be able to recall and utter them prompted by your gestures. You have, therefore, an efficient tool for evaluating what vocabulary your learners know and can utter. You just need to gesture and ask either the whole class to utter or certain individuals to say the corresponding word. We could say this is a spontaneous and instant assessment tool of your students' current vocabulary knowledge of the subject you are teaching.

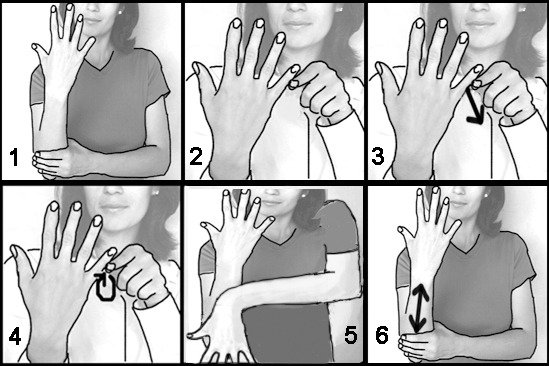

Technical language from a study of the tree.

The following example may help with the creation of your own gestures by using this as a model. Notice how we can represent a gestured 'diagram' as one base gesture (tree) with specific gestures around it. The following photos show the gestures for parts of a tree. They read: 1, tree, 2, branch, 3, twig, 4, leaf, 5, roots, 6, trunk.

We could easily add more using the same tree base gesture: 'crown', 'bark', 'taproots'... which should be intuitive in their creation. If we make a chopping action against the 'trunk', we can 'cut the tree in two'. Then show your fist as the tree 'cross section' and with the index of the other hand trace the tree 'rings' on it as though inside the 'trunk'.

Gesture study texts.

It is useful to present your learners with a 'study text', which comprises a number of sentences describing some process that needs to be studied. The study text should contain as many of the technical key words as possible. It is a way of condensing vital language into a comprehensible and meaningful and reusable description. Here is an example of the annual cycle of a tree.

We can indicate with an index moving slowly up the forearm the 'sap' rising in the tree  in spring and how this stimulates the growth

in spring and how this stimulates the growth  of the flowers or blossom

of the flowers or blossom  and the leaves

and the leaves  . Then in autumn the fruit

. Then in autumn the fruit  becomes ripe

becomes ripe

. Finally, the fruit falls from the tree

. Finally, the fruit falls from the tree  and opens and the seeds fall onto the ground

and opens and the seeds fall onto the ground  .

.

Notice I have also added gestures of other key words in the study text: 'growth', 'ripe', and 'ground'. The non-technical words should be common high-frequency words, which will add to the comprehensibility of the spoken text. By limiting our non-technical language to high-frequency vocabulary, we help our learners build the lexicon sets they need to talk about or write their own descriptions.

Recycling the language.

The teacher can now repeat this study text on future occasions in class, not necessarily word-for-word but very similar to the original. However, in future renderings of the study text you utter only the non-technical vocabulary and gesture in silence when you get to the technical words (see rationale for this). Encourage all the learners to call out the corresponding words and preferably gesture too (getting learners to gesture may depend on age, attitude and culture). If they fail to recall a word, ensure the study text is not interrupted by offering a spoken alternative. For example, you, the teacher, silently gesture 'growth' and learners are not sure of correct response. Say: "ripe or growth?" The learners now have an obvious choice and call out the latter. You carry on with the study text. This technique is preferable to a simple teacher correction.

Adding gesture to your CLIL classes in this way provides you with a further language dimension to your classes. You will be able to bridge the comprehension gap between yourself and your learners. Only too often, we teachers speak to our classes and are not quite sure how much of what we say is really going in. Through the feedback in the form of learner utterance that teacher-performed silent gestures provide, you will be more certain that the material you are teaching in your classes is being absorbed and learnt. You can also feel that not only are learners taking in the subject matter but they are also acquiring the English language at both a written and spoken level they require to express these ideas.

Article based on findings from PhD thesis (Bilbrough 2017).

References.

Kelly, S. D., T. McDevitt and M. Esch. (2009). Brief training with co-speech gesture lends a hand to word learning in a foreign language. Language and Cognitive Processes, 24:2, 313-334.

Macedonia, M., & Knösche, T. R. (2011). Body in Mind: How Gestures Empower Foreign Language Learning. Mind, Brain, and Education, 5(4), 196-211.

Pavón, V. (2018). The use of the L1 and CLIL: approaching this controversial relationship. 32nd Greta Annual Conference, 28th & 27th October, Cordova, Spain.

Tellier, M. (2008). The effect of gestures on second language memorization by young children. Gesture, 8 (2008), 219-235.

Copyright © 2021 M. A. Bilbrough

All rights reserved